When I first started fielding ideas for Diinlang a subject that causes a few headaches was that of prepositions. This area is still not completed but some new inspirations came to me last night.

English has a lot of prepositions and words that resemble them. Being English the system is irregular and words originate from many different sources.

My current working model is that these can be treated as three related groups.

The first group has directions such as up, down, forward, back, left, right, in and out. These can be treated as a point in space or a movement. Something might be “inside” or moving “inward”. In English the suffixes may not be used for some of the listed words or their use variable. I can say “up from Bill” or “upwards of Bill”. This suggests that a relatively logical and regular system for Diinlang can be constructed using “-ki” for motion and “-ru” for static as suffixes.

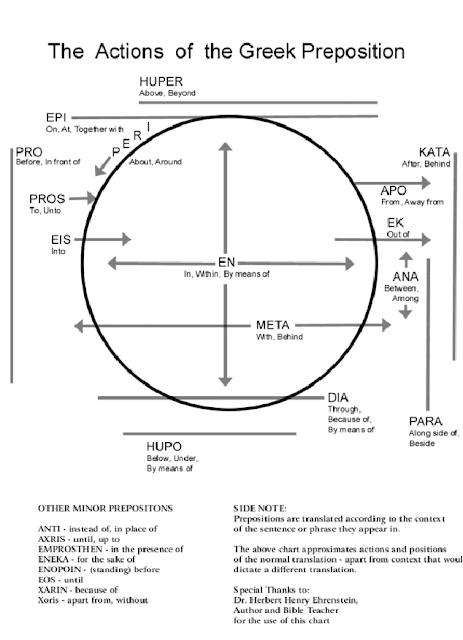

The second group are relative directions. They refer to a point relative to another point. Above, below, beside, port, starboard, before, beyond, under, on, against, abaft, abeam, super-, sub- etc. Possibly this variety can be covered by words for up, down, forward, back, left, right, in and out with some addition to indicate they are relative. Many of the existing words use “a-” or “be-”. “A-” derives from the meaning “up” or “out” rather than from the Latin “ad-” for “to”. “Be-” is Old English/ Germanic for “throughout” or “around”. Some of these words substitute for phrases such as “XXXwards of/ from” or “XXX from”.

The third group are adjectives that can be confused with prepositions and may have some overlap in use. High, tall, deep, low, thick, thin, narrow, wide, etc. To this list we can add related nouns such as height, length, depth, width, etc.

(It has just occurred to me that “etplu” in Diinlang would be more elegant than saying “etcetera” or “eksset”)

The above is not a comprehensive list, of course. I have stuck to basic linear motion and not considered circling motions, for example. In English using the above words in phrases with “to” or “from” can modify the meaning and how this can be done in Diinlang needs consideration.

The basic categorization proposed does give an idea of how prepositions in Diinlang should be approached. The basic directions/ points can be modified with affixes such as “-ki” and “-ru”. These basic words can then be modified for terms for relative directions. These words can possibly replace many of the adjectival words or create words whose relationship is clear.